At some point in our lives, we all face a dilemma that makes our stomachs churn. The public relations world presents tricky scenarios that professionals must respond to quickly, honestly and effectively. And with serious legal and reputational consequences on the line, it is crucial for practitioners to develop strong ethical codes to guide their responses. Thankfully, industry experts and Greek philosophers have proffered decision models, paradigms and guidelines to help professionals feel good about the work they do both in and out of the office.

The Codes in Place

The Public Relations Society of America requires its members to abide by its code of ethics. As a refresher, we’ve included the Code’s two key elements.

The PRSA’s six core values:

- Advocacy

- Honesty

- Expertise

- Independence

- Loyalty

- Fairness

The PRSA’s six provisions of conduct:

- Free flow of information

- Competition

- Disclosure of information

- Safeguarding confidences

- Conflicts of interest

- Enhancing the profession

The Code serves as a guide for professionals to reference when handling ethical challenges.

Ethics in Practice: the Potter Box Model

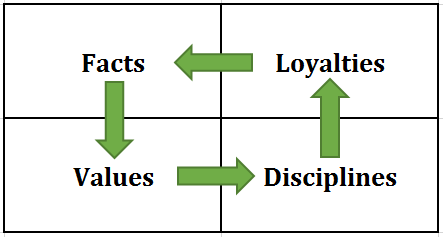

Allow us to transport you back to your college ethics class and reintroduce you to an old friend: the Potter Box model for ethical decision making.

This tool allows you to apply the professional codes and your individual beliefs to a specific situation with four steps:

Facts: What is happening in the situation at hand? What is your role in the organization or entity involved?

Values: Which of the six core PRSA values are at play in the scenario? (Hint: it’s usually more than one.) Is the situation threatening your ability to be honest with a client or public, or is your loyalty to a public at risk?

Disciplines: How would philosophers advise you to handle the situation? To which philosopher do you relate most? For example,

- Aristotle’s “Golden Mean” theory encourages individuals to perform an action because they believe in it, not just because it is a rule.

- Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperative suggests that one should act rationally, and actions should be applied universally to all situations.

- J.S. Mill’s utilitarian school of thought says the ends justify the means. If the outcome produces the greatest good for the greatest number of people, compromising some values along the way may be acceptable.

- Ross’s competing ethical duties emphasize the context. Depending on the situation, one duty may take priority over another. As a low-stakes example, when you lie to your friend to conceal her upcoming surprise party, you prioritize your duty to do good for others over your duty to tell the truth.

Loyalties: To which publics are you most loyal in this case? What other groups would be directly or indirectly affected by your decision?

After moving through those four steps, new facts may emerge, bringing you back to the start. And thus, the cycle continues until you determine the best course of action.

With these vital resources in your ethics tool kit, you’re well-equipped to navigate any sticky situation that comes your way. Take some time before the next moral dilemma to reflect on your ethical code, and you’ll be primed to make wise, effective decisions throughout your career.

Written by Clairemont intern Elizabeth Comtois, a senior at UNC-Chapel Hill.